I call it the “application saturation loop.” My friend needs a new data analytics job. He refreshes his resume and searches online for “data science jobs Chicago,” trawling through four or five job aggregator sites ranging from somewhat legitimate to completely illegitimate. He collects about a dozen jobs that could match his skill set, more or less, and he applies. Their “easy apply” online systems make sending applications relatively painless. They mostly ask him to type out his resume, again and again, in the flattest and most generic way possible. But he doesn’t hear back from any of the jobs he’s applied for. He is running out of money. He sends dozens more applications for jobs over the next several weeks. Maybe even 100. He hears back from two companies. They are both obvious scams.

Meanwhile, one of my friend’s applications becomes one of approximately 200 applications in a hiring pool. (Many other people seem to have clicked the “easy apply” button.) The hiring manager in charge of the pool becomes overwhelmed – no reasonable person could sift through so many resumes – so she does what appears to be the smart, fashionable thing and employs an “AI-based screening tool” or “online resume parser” to sift through her pool of applications.

The tool she selects claims to “go beyond keywords” to “identify applicants based on aptitude.” But of course she has no idea what it’s really doing.* After some fancy whizzing and whirring, it sends her five applications, deemed the “best” (By what metric?). My friend’s resume was not selected, but perhaps it will be by another hiring manager. Until then, his fate – his ability to pay rent and, crucially, cover our next round of Miller High Lifes – will be largely determined by job search aggregators, faceless algorithms, and the facetious whims of employers who will ask him for as many “sample assignments” as they want before ghosting him forever. There is basically nothing he can do about it.

What’s going on?

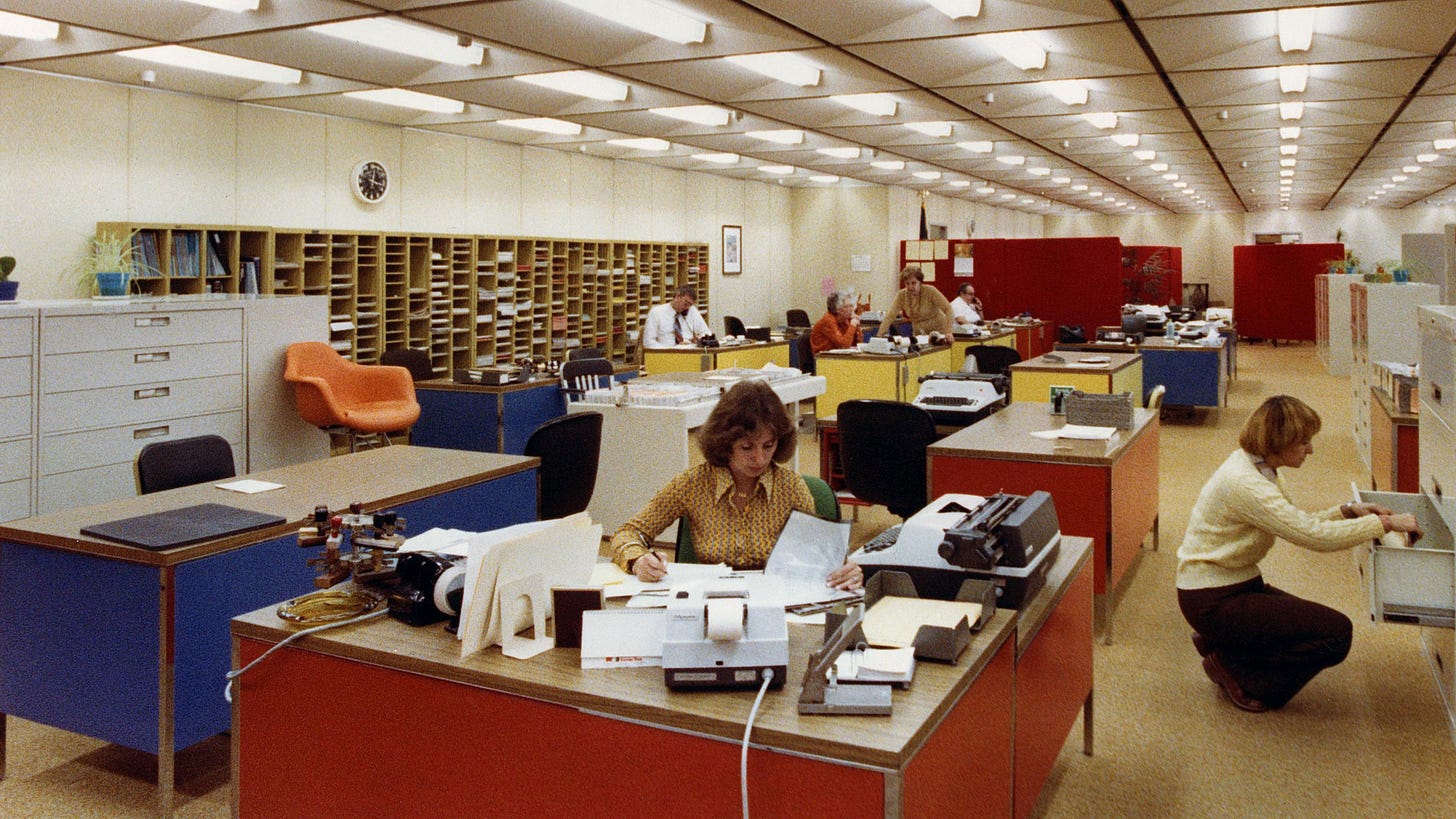

However unfashionable for me to admit around economists buoyed by “good jobs numbers,” I think the hiring part of the jobs market is broken. A job posted on one industry job board soon makes its way to 20 job aggregator sites, which are unaffiliated with the role and the firm who posted it. (They source job listings from job boards and company websites and display them on their own platform.) Unless you are lucky enough to have a pre-existing connection to a particular role, you are relying on the site to provide an active, accurate listing and to deliver your application directly to the hiring manager — and for the hiring manager to have the time to read it.

These sites once promised easier access to postings and applications, but now create an opaque maze for candidates (quick—what’s the difference between Indeed, ZipRecruiter, LinkedIn, Jobtrees, and Monster?) and a genuine headache for employers (Are you interested in reading dozens of cover letters today?). Looking ahead, I worry about how much these “tools” would make life harder in a recession, and about how other trends concerning the future of work might coalesce in harmful ways to candidates and employees.

Completely anecdotally, I’ve observed these issues again and again in the last year. Job aggregator sites encourage candidates to send buckets of generalist applications against the interests of hiring managers who receive an overwhelming number of applications that they cannot distinguish from one another. Job postings are somehow everywhere but hiring managers complain they can’t find any qualified candidates. Layoffs at prestige firms are announced left and right as companies pivot away from the pandemic’s free-stimulus-money-for-everyone era (it probably isn’t indicating an imminent recession, despite what r/layoffs would have you believe). To me, concern feels like it’s growing everywhere except the cover of the New York Times. In fact, a recent survey of 1,500 job candidates by the staffing firm Aerotek found 70% of people find their current job search more difficult than the last, even though people are more qualified than before. For the prospective job switchers out there, the path to a new role has never been more accessible in theory but frustrating in practice.

Even traditional economic indicators have begun to tell a story about the worsening broader market. What was once the “Great Resignation” during the late pandemic became the “Great Stay” as employees stay within their own companies instead of switching firms, perhaps due to fears of an impending recession or, I would argue, an inability to secure a better job. It certainly doesn’t seem like a candidate’s market anymore, and instead it feels generally safer to stay and accept your mediocre raise that barely meets the annual cost-of-living inflation adjustment.

Recently I read labor economist Guy Berger identify that unemployment increased to a 2-year high — 3.9% — in the BLS’s February jobs report, while Employ America economist Preston Mui noted that BLS quits and hires indicate it actually has gotten harder to switch jobs in the last six months. The universally positive narrative about the jobs market has begun to falter. Is it all because of AI resume screening tools? Certainly not, but the combination of a worsening market with the insidious tech trends that steer hiring have the potential to make everyone’s lives that much worse.

In an age where we’re supposed to have all this figured out, things seem to be getting harder. It’s no surprise that when the market suffers broadly, firms miss out on much-needed talent, candidates miss out on duly-owed salary increases and promotions – and the unemployed somehow have to fight even harder.

Is it all because of AI resume screening tools? Certainly not, but the combination of a worsening market with the insidious tech trends that steer hiring have the potential to make everyone’s lives that much worse.

I could shower this piece with a dozen anecdotes I’ve heard in the last year. One person who is considering switching fields because the “market disappeared” from under them. One person whose application tracking excel says he’s applied to over 75 jobs and heard back from five. One person who’s been promised a state job posting will drop “any day now” for a role he’s guaranteed to get (sorry, other applicants!). One person who gave up and became a barista.

Surely there are differences across industries and levels of expertise. And most of my friends are too young to have fully grappled with the impacts of the Great Recession. But the market doesn’t feel it’s transitioned out of the flush-with-cash pandemic years (when companies boasted the amount of PPP loans they received and consumers had more cash on hand to spend than ever before) nearly as well as economists have liked to boast. There was a unique period where low-wage, high-stress jobs struggled to hire seemingly because people had enough money from Covid checks instead. I don’t think that’s the case anymore.

I think you would be right to say that a lot of this piece relies on feelings or vibes, but that’s sort of the point. Traditional economic indicators can only tell part of the story. There’s a lot of value in the stories we hear around us, especially when they disagree with the headlines. Kyla Scanlon’s genius coining of the term “vibecession” and subsequent analysis of it speak to this phenomenon well. There are genuine divergences between economic expectations, theory, and reality. Plenty of understandable reasons contribute to this, which Scanlon notes might include misinformation, outsized media coverage, and conflating “inflation going down” with “prices going down.” But it is unmistakable that consumer sentiment feels much lower than indicators would have you believe. An AP-NORC poll last Fall concluded that 73% of respondents described the current economic status as poor, 66% indicated that their expenses have risen, while only 25% indicated that their income had risen. That’s worth paying attention to.

Concerning trends are coming together

Back to the hiring market. Even beyond what I call the “applicant saturation loop” of more job application tools and thus more job applications (which some people dumbly try to escape via ChatGPT cover letters), this hiring market has some fresh challenges for candidates.

Work from home has been great for a lot of people. But the unpredictability about its future has led firms to make wishy-washy demands about employee location at times and globalize the market beyond belief in others. One friend of mine finally secured a position, only to learn in a final round interview that his team’s actual location met deep in the suburbs once a week instead of the city. He couldn’t make it work. One recent study found remote jobs receive over twice the number of applicants for a role than in-person jobs; I strongly suspect the true number is much higher. The pandemic rapidly accelerated the increasingly global nature of jobs. You’re not competing with software engineering graduates in San Jose for the Google internship; you’re competing with everyone in the world.

This, I’m sure, has harmful impacts to employees. Why invest in them long-term when they’re vastly more replaceable? There is always some person who is qualified in some place where the cost of living is lower.

As roles go global, employers must resort to being increasingly finicky about hiring. Gone is the ZIRP era, money is real again! Maybe there’s a recession around the corner! Hiring decisions seem more serious than they were just a couple years ago, and this means candidates are subject to more tests to validate their ability. Hence more rounds of interviews, more demand for free labor – ahem, sorry, I mean “sample project work.” One-way video interviews are proliferating widely as the number of applicants for each role increases, making it easier for employers to stack up content (and effort) from candidates and take even longer to sift through it (Who wants to watch 100 videos of people talking about their college internship?) Then at the end, there’s no culture of providing meaningful applicant feedback, either. So for some candidates, the cycle repeats endlessly.

What can be done?

People will keep trying to job-hop because it’s generally in their best interest, even if it gives employers less incentive to invest in their employees. According to a recent Gallup report, 21% of surveyed millennials reported changing jobs within the past year – which is three times higher than any other generation. I am, maybe controversially, fairly opposed to job-hopping. I think meaningful work and growth take a lot of time. But I’m also increasingly aware that the single best way to get the salary increase you’re owed is by job-hopping (and it’s even getting harder to do that). New positions are typically market-rate salaries, while typical raises often don’t match market rates. One study of 18 million worker salaries by Yahoo Finance showed job hopper wages in 2021 outpaced those who stayed in their role. (In some industries, workers received almost a 12% pay increase for job hopping.)

Job hopping and one’s experience of the hiring market more broadly can certainly be benefitted by networking. I’ve never found it as painful as some people say, but I have the privilege of working in an industry that I’m genuinely interested in. But the “networking” that’s generally most relevant here is the effective kind, where your friend or your Dad knows an employer or you who went to specific target school. In this way, networking will always favor the already-privileged. There’s maybe an argument that LinkedIn has flattened the playing field a bit, but I have personal doubts about the real value of such shallow connections. (But I’m happy to be proven wrong on this.)

If there is a better model out there for candidates, it is probably applying to fewer but more specific jobs (but being occasionally willing to take risks on yourself all the same!). Accepting that you will be relevant to fewer positions, but a greater value-add to those which you are a fit for, seems to be a better allocation of time. For employers, the picture is a bit more complicated. Reshaping how we apply for jobs means potentially advertising roles with more serious “candidate requirements” to limit applicants — but not so serious that you significantly reduce the diversity of your hiring pool. We should also be working towards a cultural norm where work isn’t handed to candidates unless they are deemed very serious contenders for the position, and their work is fairly compensated. Asking someone to perform a day of unpaid labor for you is not just “informative,” it’s also exploitative.

As we continue to barrel into an uncertain economic future (don’t forget it’s an election year!), it’s critical to consider how the current structure of our jobs market impacts those who are the least connected. Our attempts to bring universal access and universal candidacy may have backfired somewhat by adding layers of complication to people who just want to be considered for roles and compensated for their labor. But only once we acknowledge these challenges can we start to address them.

*Other ways this tool can be used, according to its marketing: “AI can authenticate candidates by analyzing public data that serve as proof of candidates’ claims. Professional networks like LinkedIn, Meetup, AngelList, Github, and others can be checked for work experience and portfolios. Social media, including Facebook and Twitter, also serve as evidence to show that applicants are who they say they are.” Well, do you think it’s helping your candidacy?

If you have to learn salesmanship to get a job, might as well become a salesman and get paid for it.

Great article! This is spot on with the current state of the job market and the realties of what candidates are experiencing. I have faith that if we can find some sort of "balance" in the chaos (meaning aligning AI with human experience) then we can move the needle towards building a strategy to close the gap on this issue. With tech ever evolving, we will continue to be blindsided by the results of evolution however we can be proactive in aligning on keeping humanity - HUMAN, while using AI as a tool not a lifeline. I wrote an article about this on LinkedIn, feel free to chime in.