EVERYONE'S A FORTUNE TELLER NOW and why that's dangerous

Data-driven decision-making, an FBI raid, and Texas Hold'em

There’s nothing inherently wrong with making assumptions about the future and trying to mitigate risks. But a few months before the Trump presidency is destined to make history, the commercialization of prediction has inspired a thriving new industry with a new set of harms.

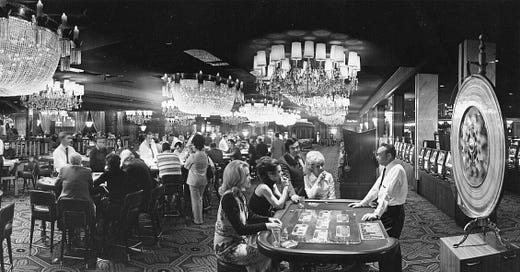

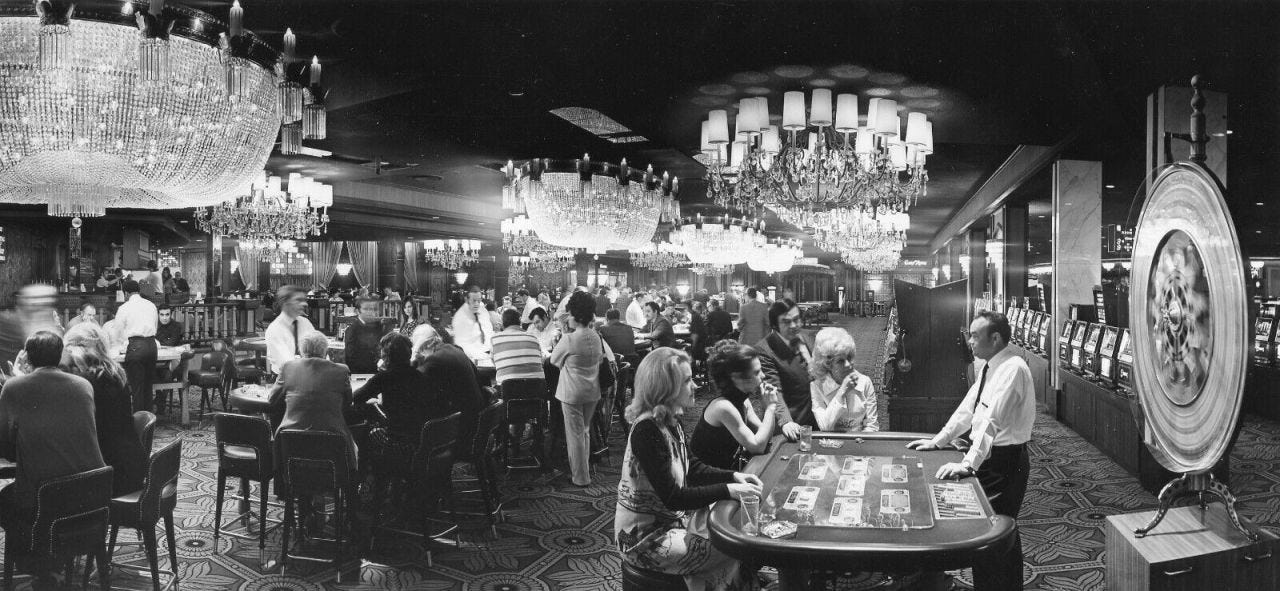

Like Nate Silver, I’ve long been surrounded by a weird intersection of politics, economics, and Texas Hold’em. As the daughter of two poker players, I spent every Christmas honing “critical thinking skills” around our oblong dining table, mastering expected value and preventing my Dad from running me off the table. It’s a great game, but as my dad always implored, we’re “just playing to have fun” – because no matter how many times I consulted the shelf of “poker theory” books beneath the TV, whether I did well or owed my brother an In-n-Out burger was in no small part determined by luck.

If it weren’t, surely Nate Silver, one of the world’s most famous statisticians, would have done better at the World Series of Poker this year. Instead, he didn’t even crack the top 50 players. While statisticians seem to outperform players with no grasp of probability, the most significant successes still appear to be dictated by the unpredictable hand of chance.

Silver’s latest book, On the Edge: The Art of Risking Everything, uses poker as a framework for managing risk and uncertainty, advocating for the adoption of greater risk in a variety of real-world scenarios. This approach marks a natural progression for someone who rose to prominence by accurately forecasting the outcome of 49 of 50 states during the 2008 Presidential election and later founded and sold the data-driven journalism platform FiveThirtyEight. From sports analytics to electoral predictions and now to poker, he has in many ways founded and steered the “prediction economy.”

Now thanks to him and a few other forces, namely the growth of algorithmic prediction powered by large language models, society’s obsession with quantification, and of course the demand to safeguard corporate profits, the practice of prediction has gone fully corporate.

Polling firms hawk prediction products and consulting giants offer market forecasts. Pundits on CNN dissect election polls with mock surgical precision, while hedge funds and market makers sift through forecasts and indicators to predict the next market-moving signal in managing their trillions. From Wall Street to Main Street, the economy of prediction offers certainty and optimization in an increasingly complex and expensive world, full of “known unknowns.”

Somewhere deep in our consciousness, humans seek to prevent and mitigate future harms. Each time you check the weather app and decide to take an umbrella to work, you are predicting and adapting. But as probabilistic thinking fully enters the public consciousness, we must consider the full scope of this economy of prediction, including its harms.

After the betting site Polymarket seemed to correctly predict Trump’s win, CNN and other news outlets praised the genius of the crypto-based predictions market. Forbes even ran the headline “Polymarket’s $3.2 Billion Election Bet Shows Web3 Potential.” The narrative seems to be something like: this group of clever underdogs got it right — and totally owned the libs! But let’s not forget:

It turns out the market was heavily manipulated by a “whale” — a French guy named Theo — who is suspected to have spent over $30 million of his own money across a variety of mostly pseudonymous accounts.

Americans can’t even use Polymarket legally. In 2022, Polymarket settled with the CFTC that it had been running an unregistered, illegal derivatives market and banned Americans from waging bets on it.

The week after the election, the founder and CEO of Polymarket’s house was raided by the FBI.

Regardless of its legality, the credibility (and ethics) of its markets was questionable from its outset. Similarly, the newly-legalized and controversial betting app Kalshi (operating in a legal gray space after thwarting shutdown attempts by the CFTC) attracted over $270 million in trading volume from the November 5th election and only started selling elections contracts on October 4th.

Kalshi, like Polymarket, allows users to bet on real-world events, like political outcomes, by effectively functioning as a centralized exchange for event-based predictions. In some ways, it’s another emblem of today’s gambling-for-the-people era, serving as Fanduel for people with political science degrees; in other ways, it introduces an entirely new set of ethical hazards. (I can’t wait until the conspiracy theorists learn about insider trading.) Regardless, news outlets and TV pundits also take these markets oddly seriously, having treated its market odds during election season like a random-sample live-caller poll with a diverse pool of respondents, instead of a market for degenerate online gamblers. Kalshi also recently scored tens of millions in VC money.

The problem, as noted by Yale Professor Jeffrey Sonnenfeld, his co-author Steven Tian, and infamous White House correspondent Anthony Scaramucci, is that these markets have incredibly thin volume and liquidity — meaning very few traders actually participate, so those who do have overwhelming influence. Additionally, legal questions bear heavily on their ability to continue operating, and they are an easy access point for foreign manipulation.

It is dangerous to lose sight of how easily numbers can be manipulated. As data journalism gains popularity for its promise of objective, math-based reporting in an era criticized for overblown partisan reporting, what seems like fact can still be assembled just as easily as narrative.

Did you know the U.S. Senate had formed a Y2K committee in 1998, and it predicted “serious” technological glitches? Even today’s finest crystal balls get it wrong pretty often. COVID economic recovery predictions were pretty much universally incorrect (along with a ton of other COVID-era predictions). The AI scaling hypothesis – that advancements in AI will scale dramatically with the amount of compute invested, and which pretty much all of our retirement accounts are hinging on – was just admitted by Ilya Sutskever, former co-founder of OpenAI, to not really be panning out. Back in 2007, recall that basically no economist predicted the Great Recession. I suppose you could argue that fraud (bad ratings from the credit agencies) was the key reason they missed, but this just further demonstrates the hubris inherent to these predictions; the future of the world is predicated on so many assumptions that we couldn’t ever possibly test.

Keynes’ “animal spirits” have yet to be tamed. The most listened-to predictions (recessions; elections; sports) are the hardest to predict because there’s simply too many human complexities for a model to take into account, even today’s most sophisticated ones. There’s a point where continued modeling just stops making sense. Has anyone ever laughed harder than statistics twitter encountering Nate Silver’s decision to run “80,000 simulations” on a binary outcome the night before the election?

Maybe this computing time would have been better spent considering the policies of both candidates. And maybe instead of poring over the simulation’s quote-tweets, readers like me could have had a martini in a nice armchair and listened to Alice Coltrane. In a world increasingly fixated on the details of probabilistic distributions and the philosophy of “data-driven decision-making,” it's easy to overlook the importance of humility when dealing with uncertainty.

A close friend of mine, Emily Sandstrom, recently interviewed Tiktok’s most famous forecasting expert for Interview Magazine. The forecasting expert, known online as Megan from Solar Glow Meditations, uses two metal dowsing rods to channel the earth’s vibrations into a “yes” or “no” to any question asked, and her videos get hundreds of thousands — sometimes millions — of views. Like more rigorously mathematical pundits and forecasters, she doesn’t always get it right, and it doesn’t really matter.

What is a consequence-free environment for Megan and other influencers is not for those making bets. Influencers, and journalism fixed on the markets as a whole, has a perverse incentive structure where being sharply attention-grabbing matters more than being right. Then, our social media ecosystem amplifies the most extreme predictions, resulting in some kind of self-reinforcing bubble where outlandish forecasts can bounce around echo chambers, creating weird artificial consensus. What begins as a contrarian view can quickly become conventional wisdom, not because it's correct, but because it's controversial enough to go viral. This is also the ideal ecosystem to support conspiracy theory.

The rise of prediction markets, forecasting influencers, and even data journalism reflects a deeper societal shift: the quantification of uncertainty can become a hot commodity. We've created an entire economic infrastructure around the practice of prediction, complete with its own celebrities, platforms, and financial instruments. But as with any rapid commercialization, we should consider who really benefits from this transformation.

Some winners I can think of:

Market makers taking fees regardless of outcome

Media outlets getting engagement from prediction coverage

Politicians using markets to claim momentum

“Prediction influencers” building their personal brands

Large players who can move markets

The losers, unsurprisingly, tend to be you and I, outsiders gambling online or just making decisions based on weird assumptions from media and markets. When we pay so much attention to quantification in the media, we risk losing the underlying stories and philosophies that accompany qualitative narrative.

Perhaps it's time to rediscover the virtue of epistemic humility. Like a good poker player who knows that probability is a guide, not a guarantee, we might be better served by approaching the future with a blend of careful analysis and humble acknowledgment of what we cannot know. After all, the most dangerous prediction might be the belief that we can predict everything.

The commercialization of prediction won't go away – there's far too much money and too many careers invested in it now. But as consumers of these predictions, we can choose to engage with them more critically, recognizing that behind every forecast lies a set of assumptions, behind every prediction market is a set of incentives, and behind every confident proclamation about the future sits the unchangeable fact of uncertainty itself. My dad’s poker table wisdom reminds us to humbly play for fun because the future will unfold as it will. Our goal shouldn’t be to predict it perfectly, but to maintain our ability to adapt and respond well when it inevitably surprises us.

great piece. epistemic humility indeed. i have one teeny tiny nit: Y2k isn't an example of a failed prediction. Widespread disruptions were avoided precisely because an army of programmers foresaw (not predicted ha!) the issue and harangued their bosses with horror stories to convince them to put money and time towards fixing it.

It's actually a pretty inspirational story of humans cooperating across industries to solve a potentially disastrous issue.

I like to repeat periodically my own personal moto to stay humble: I’m just an idiot like everyone else doing my best job to not be a complete moron.