how to predict a recession

be the federal reserve chair that you want to see in the world

I spent $12 on eggs this week, and they’re not even free-range.

I’m not sure if it’s the avian flu or greedy corporations or UwU shy hens, but it doesn’t feel as though the prices of grocery staples are going back to normal1 anytime soon. Consumers like me are left to our own devices to justify such costly, luxurious meals as making pasta at home.

The pasta at home.

And it’s not just grocery inflation – fear of the “economic future” is everywhere. Major outlets hawk the same doomsday narrative that my worried, underemployed friends do over wine at dinner parties. Whether its unemployment or interest rates or Treasury yields or housing development, one person might tell you we’re fine but somehow the next two will predict the end of the US Dollar.

This creates a challenging environment for people like me who, against popular understanding, do not work in finance and do not earn a salary at or above my city’s area median income. Should I be saving? Should I be spending? There are moments when I feel I’d get a better return by spending my time scouting for first-edition e e cummings texts at thrift stores than buying the index funds my coworkers talk about at lunch.2

Conventional Metrics Are Weird!

As I’ve gotten older, I’ve begun to realize there is no all-knowing Mister Market who tells me what to do with my money to make the best of tomorrow’s economy. In fact, the very tools we rely upon to study the market reveal deep flaws in themselves the deeper you look.

Fundamental concepts like Price Theory, the Efficient Market Hypothesis, and basically any equation found in an MBA textbook rely so heavily upon on the existence of perfectly rational firms and consumers — assumptions critiqued in every discipline outside of economics (except, of course, for business) — that their universal application contributes to deep misunderstandings about markets and human behavior. I noticed this on a personal level too, despite taking several microeconomics classes and reading hundreds if not thousands of sharp takes by business geniuses on the Internet. For example,

You can buy a copy of Umberto Eco’s “The Name of the Rose” at basically any used bookstore for $2, but my friend chose to buy an identical new copy for $25.

Cheeseburgers seem to degrade in quality as they get more expensive.

A company which is seemingly incapable of ever producing a profit can be worth $500 million — or more.

Economists might speak to “consumer preferences” and “unique market characteristics” and “infinite growth money go up forever,” but you and I can recognize the fallibility of their defenses. They can’t explain everything.

By extension, the conventional economic metrics we use to make predictions are also imperfect. Indicators long heralded as the gold-standard, like the inflation rate or the BLS’ reporting on the jobs market, are probably not as reliable as many think (I’ve learned more about this from researchers like Blair Fix3). Inflation in particular is often misunderstood by journalists and further misunderstood by their readers (Year-Over-Year presentation seems to confuse a lot of people about its implications. Prices were still high in 2022!)

So, when it comes to the big things, like predicting an economic downturn severe enough to be called a recession, it’s important to look beyond the standard macroeconomic outlook. Sure, there might be some weight in metrics like Treasury yields or the unemployment rate, but they’re ultimately not foolproof.4 These metrics often obfuscate the increasing precarity of those most impacted by an economic downturn - think of the gig economy workers careening from job to job, the single mothers who lose their full-time salary with healthcare and must turn to several part-time roles instead. They might be recorded as, quite simply, “employed.”

Time To Get Creative!

The economy has gotten more complicated, and so too have the methods necessary to understand it. It should come as no surprise that you now need a TikTok account to get ahead of standard macro indicators and ensure accurate predictions.

Here’s a sampling of some essential metrics you should be evaluating:

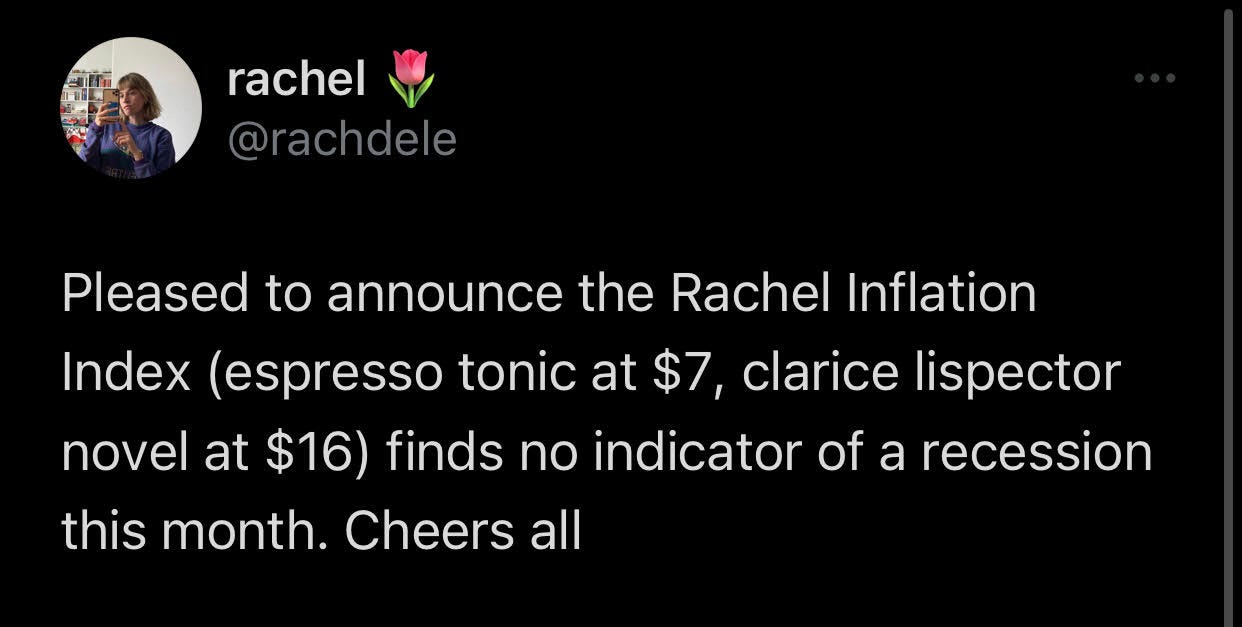

Instead of reviewing typical inflation statistics, create your own basket of staple goods and evaluate price changes. Perhaps include some classic consumer staples like Glossier Balm Dotcom, black sesame seeds, and Vyvanse?

Instead of the employment rate, tweet about buying a $13 cocktail, and contrast the number of men saying nice! to the number of men who tell you to save your money, idiot. That could have been a mortgage.

Instead of looking at recent Federal Reserve interest rate decisions, count the number of startups promising to optimize a task by making it more complicated.

Instead of the Housing Market Index, track the price of a Manhattan basement apartment without heating, AC, or a window.

Also, is Nick Cage in a bad movie? If yes, one of his properties isn’t selling at his asking price.

I also recommend utilizing a highly-reliable metrics, ones that have predicted every economic downturn before, such as:

Times my cat picked his straw chew toy over his spinning wooden ball toy. (Consistent preference for straw chew toy? You guessed it: housing market collapse).

Number of columnists at the New York Times telling you Actually, Your Life is Pretty Good, or my personal favorite, Rent Going Up? Get Over Yourself, Millennial.

Normal = Pre-Pandemic? Does anyone know anymore?

Please remember when you go to dunk on this piece online that everything in this post constitutes financial advice.

Blair’s piece is here: The Truth About Inflation – Economics from the Top Down