Since roughly the start of the pandemic, unemployment among new college graduates has been higher than that of the general population – and it continues to grow.

The media is picking up on this headline as though it were one of Zohran Mamdani’s wedding photos. Fortune recently lamented that new grads have been “locked out” of work due to a sluggish post-pandemic labor market, tariff implications, and the widespread adoption of AI. Vox referred to the job market for new grads as “weird,” while Fast Company and NBC News noted that companies should take notice that their entry-level jobs are disappearing. The Atlantic even argued AI is stealing these 21-year-olds’ jobs.

And let’s not forget how many fellowship and internship programs have been cut this year – from the classic Fulbright to the historic Presidential Management Program and countless others from the at least 400 National Science Foundation grants for STEM education that were cancelled. Meanwhile, grad school applications are on the rise, as young people try to escape the labor market. This April, the Law School Admissions Council reported that applications are up by a whopping 21% this year.

Call it the “white collar recession” or the “AI doom spiral” – the slow-moving white collar job market has made it hard for kids fresh with bachelor’s degrees in Leninist Theory and three-month internships in Steve Bannon’s dungeon to gain their first foothold in the economic ladder. In May 2022, the unemployment rate for recent college grads (aged 22 to 27) was 3.9%. In March 2025, it was 5.8%.

Also, recent BLS data suggests that the youth (15 to 24 year olds) unemployment rate has also ticked up somewhat, from a low of 6.6% in 2023 to a recent high of 9.7% in May 2025.

Even if these unemployment increases appear modest, I’ve recently observed the Generation Z (age 13 to 28) people in my life get sandwiched into roles that don’t seem to fit them. A bright communications grad with multiple internships making flat whites. An art history grad watering plants in the office buildings downtown. A psychology grad tending to honeybees – part-time. Countless posts on the r/jobs subreddit that are some variation of “Why is finding an entry-level job so hard now?”

Is it just a correction following the late-pandemic white-collar boom, or is Gen Z experiencing a recession of their own? The articles cited above will toss around AI, interest rates, tariff anxieties as all potential causes – but lately I’m more interested in the effects.

In addition to providing necessary workforce training that benefits both the employee and the company, entry-level roles function as critical stepping stones to those in them. They teach the lowest common denominator of the industry and allow one to progressively oversee more and more of it.

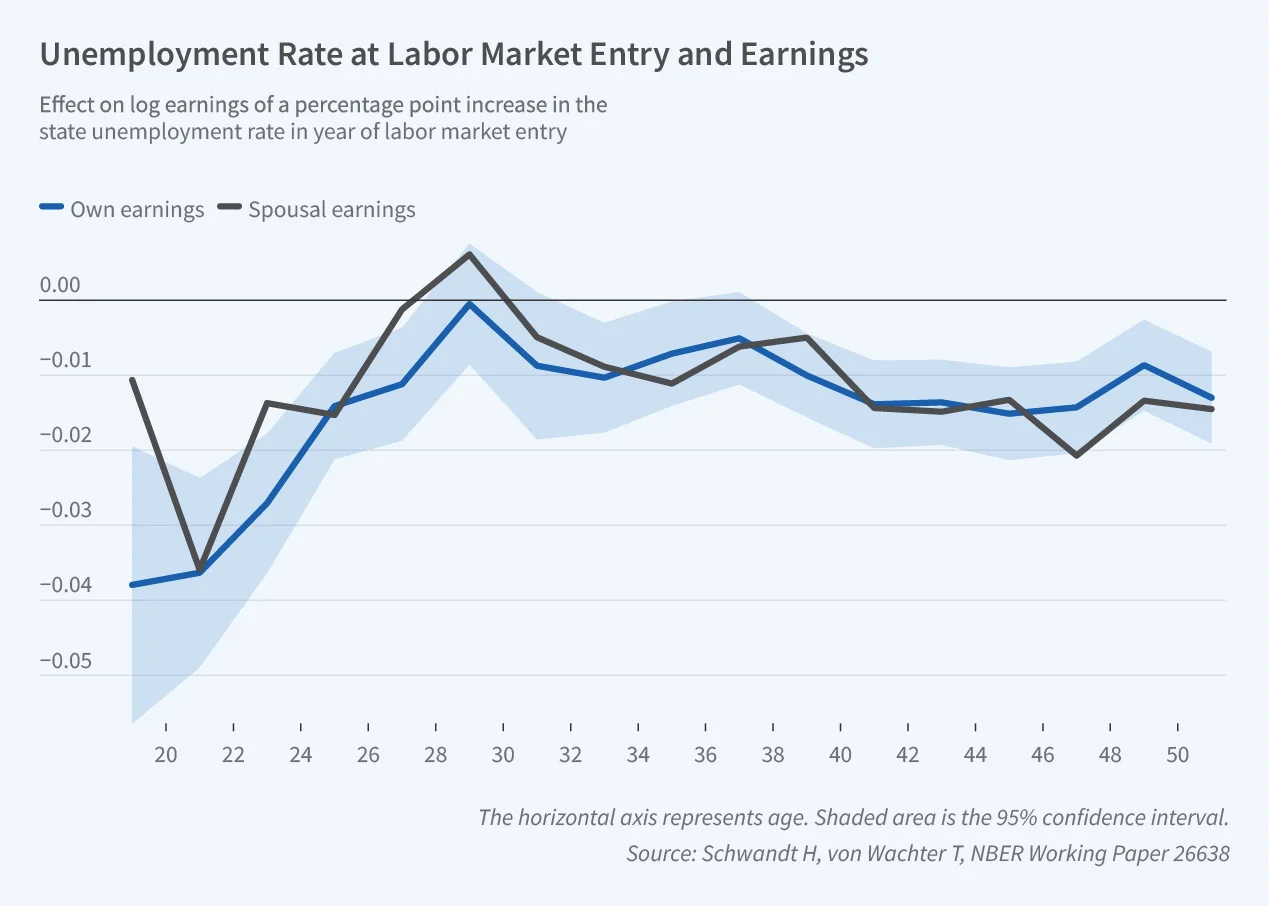

As these positions erode, the typical pathways to long-term career progression disappear alongside them. We know that Millennials who graduated around 2009 into the Great Recession had enduring financial challenges long after it officially concluded. Academic economic research supports this, with recent work concluding that students who graduate into recessions have a myriad of long-term consequences to their careers. One paper by Hannes Schwandt and Till M. von Wachter finds that “leaving school for work during an economic downturn has negative consequences later in life for socioeconomic status, health, and mortality.” They also “have lower long-term earnings, higher rates of disability, fewer marriages, less successful spouses, and fewer children.”

When I left undergrad, I was proud to secure an entry-level role at a think tank, so much so that I didn’t really care that I only made $34,000 a year. One, it was largely enough to pay for my $750 rent, a cheeseburger after work, and camping in Maine once a year. And two, I thought it meant I had locked in a lifetime of cool jobs. I failed to understand how fragile linear career paths are – how vulnerable they are to macroeconomics, random chance, and the whims of managers.

I worry that joblessness and under-employment in Gen Z will fuel its already existential nihilism. Already called the “nihilism generation” (also by Kyla Scanlon) in part due to their perceived impending doom, Gen Z faces fewer roles to apply to and steeper competition for those roles that do exist. The job market itself has changed, somewhat for the worse. Last year, I wrote about how “resume parsers,” listing sites like Monster, and other tech interventions into the job market make it more challenging for everyone involved. There’s the vicious application saturation loop: people click Linkedin’s “Easy Apply” button hundreds of times (because it is “easy”!) until there are thousands of applicants for each role – until life becomes hell for recruiters (almost forcing their hand to use AI resume parsers that screen for a black box of characteristics) and candidates disappointingly receive hundreds of rejections.

Looking at the bigger picture, almost every headline about Gen Z follows the same pattern: young people are drinking less, partying less, spending more and more time at home alone. Isolation, exacerbated by economic precarity, is a tragically reinforcing cycle. As these crises intersect, young people struggle to retain the lifestyle of their older siblings and parents – who spent their 20s making friends, vacation memories, the mistakes that become personal growth, and ultimately a life for oneself.

Given this backdrop of isolation and social strain, it’s not surprising to me this is also the generation that supported Trump in unexpectedly high numbers. Like accelerationism, it’s a rejection of the status quo. The critical question now is if this generation can be re-engaged – if they can be convinced that conventional American society is worth reclaiming after all.

I’m a recent college graduate with a degree in Geography and this is reflective of my experience - the entry-level planning and GIS positions which I had banked upon appear to be increasingly non-existent, especially given Trump’s cuts to the funding streams necessary to finance environmental studies and public works projects. I’m not completely giving up hope, but it seems increasingly likely that I’ll be stuck in a part-time position unrelated to my major for far longer than I might’ve expected to be. There’s always the prospect of moving (lots of jobs in places like Columbus, Ohio or Denton, Texas) but for those consigned to particular region of the country, it is beginning to feel impossible.

A compounding explanation for the lines on that unemployment rate graph is that the value of a US undergraduate degree is approaching zero.